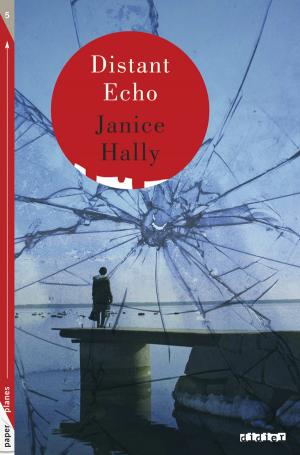

When Dr. Lelong arrives in Toulouse to examine a young American woman with amnesia, he thinks she is simply an intriguing psychiatric case. But there is nothing simple about Marilyn Jensen's amnesia. She has a completely new personality, and even a new language: French. As his feelings for her become stronger, the mystery of her condition deepens.

When Dr. Lelong arrives in Toulouse to examine a young American woman with amnesia, he thinks she is simply an intriguing psychiatric case. But there is nothing simple about Marilyn Jensen's amnesia. She has a completely new personality, and even a new language: French. As his feelings for her become stronger, the mystery of her condition deepens.

A psychiatric thriller in the best tradition, Distant Echo keeps you guessing until the end.

AUDIO VERSION

Chapter 1

I

Cogito ergo sum. Je pense, donc je suis. I think, therefore I am.

Lost in my thoughts, I looked out of the train window and saw the curve of the viaduct ahead and a spectacular gorge below. I suddenly realised that the train was speeding through the heart of the South West toward Toulouse, and I would soon be face-to-face with the enigma of Marilyn Jensen.

I think, therefore I am.

Establishing that we exist is a start, but Descartes didn’t continue the discourse with the question: “I am… but who am I?”

When I was a student, this was always the source of much debate. Psychology, psychiatry, medicine, philosophy, religion: all proffered theories, but none could completely explain the essence of a person’s individuality, their personality, their spirit.

What made me so different from Philippe Rohart, for example? We had taken the same classes, passed the same examinations, gained the same qualifications. So what had motivated him to create his empire within the medical system, but compelled me to escape it? And why, since he had little but contempt for my choices, had he telephoned me first thing this morning, anxious for my help?

The little buffet cart rattled to a stop beside me and I bought a coffee. As the water dripped through the filter into the plastic cup, I thought back to eight o’clock that morning in my apartment in Paris. Philippe had used his secretary to place the call. He did it to ensure that I realised how important he was these days. She had informed me that “Dr Philippe Rohart, the Chef de Clinique of Hôpital Casselardit in Toulouse” was on the line, and paused as if giving me time to stand to attention before announcing that she would connect me to him.

I almost expected a musical fanfare, but after a brief pause Philippe came on the line, breathless, hesitant “Hello? Alexandre? Hello?”

I detected a small tremor as he observed the pleasantries of asking how I was, and what I was doing these days. He was doing his best to be sociable, but it was clear that he had a favour to ask and was nervous about introducing the subject. I enjoyed prolonging his agony by telling him about my latest book. Even across the phone line I could hear that he was congratulating me on my success through clenched teeth.

Finally, I allowed him to divulge his business. He launched into the story of Marilyn Jensen, an American tourist who had fallen from a mountain path at Saint-Cirq Lapopie.

“She was in a coma after the fall,” he told me, “Now she has regained consciousness, but is exhibiting retrograde amnesia.”

“So she can’t recollect the accident. That’s not unusual.”

“More than that, Alexandre. It’s global. It’s not just the accident that’s a blank. She can’t remember anything about herself. Doesn’t recognise her fiancé. He was at her side while she was comatose, but since she regained consciousness, we’re not permitting him to enter her room because it’s too perturbing for her. She has no idea who he is. I’d like you to come and have a look at her.”

I’ve encountered amnesia often in patients. It can take many forms. It can be caused by trauma, physical or mental. It can be caused by tumours, cerebral seizures, or degenerative disease.

Sometimes the memories are still there, hidden in some cranial cache, and they can be accessed again as if recovering data from a faulty computer’s hard drive. Sometimes the memories, and the person that they formed, are lost forever.

I had studied in the USA, and I assumed Philippe was calling me in because he wanted someone proficient in English to help with the case of this young American woman. But then he explained how it was more complicated than I realised.

“There was a slight cut on the left side of her head. No fractures showed in X-rays. We’re doing a CT scan to see if there is any injury to the left hemisphere of her brain. At the moment, she seems to have a form of aphasia. She cannot comprehend or speak her native English.”

I didn’t understand: if she had lost the ability to talk, how was she communicating with them about her amnesia?

“It’s the strangest thing, Alexandre,” Philippe continued, “she understands and can speak perfectly… in French.”

II

I could smell the distinctive odour of disinfectant the moment I entered the hospital and instantly felt an intense emotional reaction. I was transported back fifteen years to an unhappy internship. The sight of Philippe Rohart took me back, too. The hard fluorescent lights reflected off the floors and walls, and off Philippe’s round face, and the dome of his head, too. He looked up at me, forced a smile, and shook my hand. “Still have your hair, I see!” He made it sound like an accusation.

When we were students he was always emerging from the shadows to appear at my side, always standing a little too close, always intruding on conversations with the girls that spoke to me, and always – I sensed – resenting me for it.

So now, it seemed I was somehow to blame for his hair loss.

“Sorry about that. It’s genetic, I guess.”

Philippe snorted through his nose and gestured for me to accompany him. As we walked, he nodded to the left and right at his subordinates so that I would be in no doubt that we were negotiating the corridors of his empire.

When we reached the Department of Medical Psychology, Philippe excused himself while he collected the results of the CT scan, leaving me to introduce myself to Marilyn Jensen’s fiancé.

Richard Berberich looked a little younger than I, perhaps around 35 years old. His eyes were red and shadowed by fatigue. He paced the hospital corridor sipping on a coffee as he spoke. “It’s very difficult for me. She doesn’t know me. In fact, it seems to upset her whenever I’m present.”

“That’s normal.” I tried to console him, “It’s not personal. If you can imagine being in her position, you’re a stranger to her. It would be very difficult to accept if a person you don’t know insists that he has a special place in your life.”

“I haven’t been able to insist on anything, Doctor Lelong.” Lack of sleep was making him irritable. “She says she doesn’t speak English. She can’t understand me. How is that possible?”

I took a deep breath and paused for thought. “I have seen cases of brain lesions, due to trauma or disease, which have caused people to be unable to comprehend or to speak. I have even observed cases where a person’s voice changed, or they acquired a speech impediment making it difficult to pronounce certain words or sounds: people have acquired strange accents and sound like foreigners.”

Berberich gave vent to his frustration, “She’s not speaking English with a French accent, doctor, she’s speaking French!”

I had to admit that I had never encountered a case of someone who was able to speak another language. “Could she speak French well before the accident?”

Richard Berberich explained that she had studied it. “But she certainly wasn’t fluent. She never spoke it much at all.” He shook his head slowly to himself. “This was a dream holiday for her: her first visit to France. I wanted us to go on a cruise in the Caribbean. No offence, but I wish I’d never let her persuade me to come to this damned place.”

I nodded and smiled politely, trying to make allowances for his fatigue, confusion, and concern for his loved one; but my patience seemed to aggravate him.

“So they tell me you’re some kind of expert on this? What are you… doctor, therapist, brain surgeon?”

“I am a physician, but not a neurosurgeon. I’m a qualified psychiatrist. And I spent several years in the US studying clinical psychology. I work mostly in the field of therapy, now.”

“A bit of everything, then. So in your expert opinion, doctor, how long can this condition – whatever it is – last?”

“Hours. Weeks. Years.”

“You have no idea, in other words.”

I shook my head. “I’m sorry. There’s no point in offering false comfort.”

“Well is there anything you can offer?”

“I need to see the result of the CT scan. And of course I need to talk to Marilyn. I’d like to understand what’s happening inside her head.”

“Yeah?” he said, “Wouldn’t we all.” He turned and walked away down the corridor.

III

Normally, in cases of aphasia, where difficulty of language comprehension and speech are concerned, there is evidence of abnormality in the left hemisphere of the brain.

Philippe Rohart and I examined the results of the CT scan in the small office I was to use for the duration of my stay. Although Marilyn had suffered a blow to the head, the scan showed no lesions on the brain. That was a positive sign. But it only added to the enigma of her loss of English and adoption of the French language.

I was impatient to see her and hear her myself.

Philippe Rohart walked me along the corridor and stopped outside the door to her room, as if delaying the moment of revelation for dramatic effect.

“Alexandre, I’m counting on you… The press are asking questions. Marilyn Jensen is a sensational case. We need to know if her symptoms are authentic.”

“Authentic?”

“Her French isn’t perfect, but that’s not the point. Your English is better than mine. You spent five years in the USA. I thought maybe you could dupe her into saying something in English.”

“Dupe her?” Suddenly I sensed my status as an expert disintegrating. “That’s why you asked me here? To play verbal games with your patient?”

“No Alexandre. Don’t be ridiculous! This is a fascinating case. There’s probably a story in it for you: you have a chance to make even more of a reputation for yourself.” Philippe’s words had a certain tone. He had entered the hospital system and worked his way up to the top, but his success wasn’t enough for him. I work in the private domain, experimenting with new theories and techniques. I write books and articles for magazines, from time to time I’m invited on television or radio programmes when they need an expert opinion. I’ve had some famous patients at my private clinic, and so, although I’ve never been avid for publicity, my name appears quite regularly in the media.

On those rare occasions when I encounter Philippe, he gives the impression that I did all of it just to make him feel bad: unimaginative, traditional, conformist, predictable – his words, not mine. The refrain was old, and I was tired of it. I was beginning to regret travelling all the way to Toulouse.

But then he opened the door to her room.

IV

Marilyn Jensen’s skin was ghostly white, merging with the sheets around her. The tresses of her hair radiated on the pillow like golden ribbons. When we entered the room, her eyes opened: two chips of lapis lazuli – piercing, brilliant blue.

Philippe greeted her in French and introduced me. I shook her hand. It was small and fragile. I found myself holding it for longer than necessary as I looked into her eyes. She made no attempt to draw it away. I released it gently and took a seat beside the bed.

I looked at Philippe and raised my eyebrows in a signal for him to leave. He excused himself with a certain indignation and left, but I supposed he would be listening through the door.

I turned to Marilyn to find that her eyes had never left me. I explained that I would like to ask her some questions, and asked if she was agreeable to that.

“You can ask, Doctor Lelong, but I can’t

promise to give you answers.”

When she spoke, I listened for the trace of an American accent but her vowel sounds were more reminiscent of someone from the south of France. The mystery of her condition captivated me.

If I were honest, she captivated me.

Ask for chapter 2!

|

I

I plunged into the swimming pool. The shock of the cold water revived me after the intense heat of the day. I put all my energy into swimming one length as fast as I could, then turned on my back to continue at a more relaxed pace and consider what I had learned from my first interview with Marilyn Jensen. I had established many things, but for each thing I learned, ten more questions presented themselves. Marilyn’s boyfriend, Richard Berberich, had told Philippe Rohart that she had studied French when she was young and had recently been having private classes. But when they arrived in France, he had observed that she had problems understanding people when they spoke, and had difficulty answering them. That was not unusual. When I first went to the USA, I quickly discovered that the English people spoke had little relation to the English I had learned at school. It had taken me a long time to decipher the various American accents and to respond fluently. Was it possible that this process had accelerated when Marilyn was unconscious? Had she lost the inhibitions which stopped her from accessing the French vocabulary in her possession? During my interview with her, she chose the correct words easily. Any hesitancy on her part was not linguistic, but due to confusion about her condition. She was perturbed that people insisted she was an English speaker. Although some English words were familiar, she could not understand complete sentences, and she found it impossible to form the words to speak. I got out of the pool, got dressed and took the elevator up to the studio I had rented for my stay. I opened my laptop computer and created a file for the notes about my new patient. Aphasia can manifest itself in many ways: people can lose the ability to comprehend, but be fluent in speech; or they might be able to comprehend but unable to speak; or they might lose both speech and understanding; or indeed manifest any combinations of these symptoms in varying degrees, dependent upon the damage to the different areas of the brain. It was important, therefore, to do more detailed investigations to discover which parts of her brain were affected.

II

“It would be nice if someone would keep me informed, is all I’m saying!” Richard Berberich’s raised voice echoed along the corridor as I approached. “I presume we’re going to be paying for this, yes?” Philippe looked even shorter than usual as the American towered over him. Seeing me approach, Philippe seized his chance to escape: “Dr Lelong,” he said, addressing me formally, “apparently no-one told Mr Berberich that you had ordered an MRI scan…” To Philippe’s relief, I led Berberich away down the corridor and into the cafeteria. I suspected that the last thing he needed was more caffeine, but at least we could talk in private there. I explained that I had ordered an MRI scan to discover if there was any damage that had not shown on the CT scan. “The CT scan localises haemorrhaging or lesions, but the more sensitive detail in the MRI scan can show if there is axonal damage, which could occur without evidence of bleeding or trauma,” I told him. “And what is… axonal damage?” he asked. “Axons connect the white matter and the grey matter in the brain.” I tried to describe it in terms that would be easily understood. “The white and grey matters in the brain have different densities, and in a situation where the head suffers some kind of acceleration and deceleration, such as a car crash or a fall, they travel at different speeds back and forth within the skull, effectively tearing the axons.” “So there can be damage without blood clots, or fractures, or other things that X-rays and CT scans would show you…” “Exactly” I replied. “And so this MRI scan will cost how much?” Berberich asked. “A fraction of what it would cost in an American hospital. I suspect that Ms Jensen’s insurance company will be astonished at how reasonably priced our services are.” I smiled. Berberich did not. “Cheap treatment doesn’t impress me,” he said. “We have excellent insurance. Our insurance company will be happy to fly her back to the USA, if you’ll permit her to travel.” I was surprised. “Have you discussed that with Ms Jensen? Does she want to return to the States?” Berberich’s face reddened and his eyes fixed me menacingly. His jaw muscles clenched as he contained his anger. When he spoke, his tone was level and strangely soft. “Point A, Dr Lelong: I couldn’t discuss this with Ms Jensen as she was not here when I arrived this morning. Someone had taken her for an MRI scan without informing me. And Point B,” his control began to falter, “even if Ms Jensen had been here, she doesn’t understand me because apparently I’m speaking a foreign language!” I nodded. “I apologise for Point A,” I said, trying to remain polite. But I couldn’t prevent myself from adding, “In France we normally take the course of action that’s best for the patient without discussing the cost of it with the patient’s friends first.” Berberich’s eyes narrowed and he took a deep breath. Sensing an impending explosion, I continued quickly, “But concerning Point B, let me assure you that I’ll be happy to discuss the subject of travel to the USA with Ms Jensen as soon as we have established that there are no immediate medical problems. And you’ll be pleased to know that the results of the MRI scan will bring us one step closer to that.”

III

Marilyn was dressed and sitting in an armchair when I entered her room. Her long hair was loosely piled up on her head and held by a clasp. Her eyes sparkled, I thought, but on closer inspection I noticed that the effect could be attributed to mascara. She was making an effort to look attractive. Was it for me? The look she returned answered my question. I turned my focus to her medical dossier and noted, on a professional level, that she was taking care of her appearance. The confusion and frustration of aphasia often causes patients to become depressed. If she was feeling optimistic and cared about her physical appearance, it was a positive sign. “What news, Dr Lelong?” she asked. I detected again the slightly flat vowels in her colloquial French. Were these perhaps the sounds she heard from the Toulousain nurses while she was unconscious? I placed the results of the MRI scan, my papers, and pen on a small coffee table between us. “Well, there are signs of injury but they are very minor and not in the area related to comprehension and speech. They probably explain your memory loss.” “They’re minor. So that’s good news.” “It’s good that any damage is not more severe, but it doesn’t mean that you’ll regain your memory. And it doesn’t help us to explain your linguistic…” I hesitated. I wanted to say 'difficulties' but it seemed absurd to describe her situation like that when she had no difficulty understanding and speaking French. “Predicament?” she suggested. I nodded. “I’d like you to do some tests so that we can check to see if any other brain functions are affected.” I pushed a questionnaire and my pen across the coffee table towards her. She looked at the questionnaire. “What sort of tests?” “Nothing too onerous. Just some questions – puzzles if you like – to test your organisational abilities, abstract reasoning, problem solving.” “Like… how to solve the problem of an American woman turning French?” she laughed. I couldn’t help but return the smile that lit up her face. She was displaying a sense of humour. It meant that there were parts of her character which were intact. “Have you considered, Dr Lelong, that becoming 'French' may not be a problem for me?” she said. “Are you sure about that?” I asked. “What about your job… your life in America?” “They tell me I’m a lawyer. The loss of an American lawyer is probably a good thing for the world, wouldn’t you say?” she smiled again, and I found her eye contact disconcerting. I looked down at my notepad. “That’s a very interesting thing to say. In other words, you haven’t forgotten what people think of lawyers?” “Or what a litigious society America is?” She considered this for a moment. “No, doctor. It’s strange but I feel I know these things.” “What else are you aware of knowing? Can you name the president, for example?” “Sarkozy or Obama?” she asked. “It’s funny, because I’ve been thinking a lot about what I do know, rather than focusing on what I don’t know. And I feel much better as a result. I know things about the world, about history and so on. You know, I think if you were to ask me for a legal definition of 'Tort Law' I could give it to you.” She suddenly stopped. “Oh dear…” she grimaced, “I wasn’t a personal injury lawyer, was I?” “I think you’d have to ask Mr Berberich. I believe he works for the same law firm.” “Sadly, I can’t understand a word he says.” I noted that she didn’t genuinely appear to be saddened by this fact. She turned away and looked out of the window. “Is he really my fiancé?” “He says so, but you didn’t have a ring when you were admitted. An engagement ring is traditional in America, isn’t it?” “Yes, and if he’s a lawyer, I’m sure he could have afforded a big one.” Marilyn continued to stare out of the window. “It makes you wonder, doesn’t it? Maybe he pushed me over the cliff. Maybe that’s why I can’t remember. Maybe I’ve blocked the memory from my mind because it’s too painful. Maybe he took the ring off my finger before he pushed me over. Or maybe we argued and I threw the ring at him, and it’s lost… and… and that’s why he pushed me…” I wanted to say something reassuring to her but I thought about Berberich and his aggressive manner and hesitated. Suddenly I became aware that she was looking at me and smiling, “Do you think I read too many mystery novels, Dr Lelong?” “Do you think you do read mystery novels?” “Do I?” She thought for a moment. “Well, yes. I think I do. So that’s something I know about myself! A piece in the jigsaw puzzle.”

IV

We searched that morning for any other pieces, no matter how unrelated. And a name came up. “Elodie.” she said. “The name Elodie, seems to be so familiar.” “You think you know someone called Elodie?” Marilyn turned to me, frowning, “No, the thing is, when I first regained consciousness…” She couldn’t bring herself to finish. “This is going to sound too stupid.” “Tell me, Marilyn.” “Marilyn! That’s just it. Everyone was calling me Marilyn. The name signified nothing to me. If anyone had asked me what my name was, I would have said… Elodie.” “Can you remember anything else from those first moments?” “I was dreaming about the sea. I’m still having dreams about the sea. Waves crashing on a rocky coast. I don’t remember anything else.” I took some notes. “When you wake in the mornings, try to remember any dreams you might have had. Keep a note of them.” “Do they mean something?” “They might.” I gestured to the questionnaire and pen on the table. “Now, you have some other puzzles to solve, remember?” “Yes Doctor.” Her tone was like an obedient schoolgirl. I picked up the results of the MRI scan and my papers and stood up. “You’re not going, are you?” “I promised to tell Mr Berberich the results of the scan.” “He doesn’t have any rights over me, does he? He doesn’t have to sign anything for me. I mean, I know he’s listed as my next of kin but–” “He has told the administrative staff here that, as far as he knows, you have no family.” “That could mean either my parents are dead, or I just didn’t introduce him to them.” She shook her head. “I can’t picture parents. Maybe I was an abandoned baby, brought up in an orphanage with no-one to love me…” she raised her eyebrows, “like Oliver Twist! You see? Evidently I’ve read Dickens, too.” “Evidently,” I said. “All these books… what language do you think I read them in, Doctor?” “English, I’m sure.” She shook her head. “How is it possible? It’s just a jumble to me. It makes no sense at all. You’ve no idea how terrifying it is to have someone talking at you, making these alien sounds… how can it be that I don’t understand?” “It can happen. Some people are worse off than you – they have no means of communicating. They open their mouths and make noises. They think they’re making sense but no-one can understand them. At least you have found French. At least we can communicate.” She smiled at me. “Yes. I count myself lucky for that.” The look in her eyes was intense and disconcerting. I forced myself not to respond and changed the subject. “Would you like me to try to search for information about you, to see if we can prompt any memories?” “About me, Dr Lelong? Or about Marilyn Jensen?” It was true. Marilyn Jensen tumbled down a rocky escarpment at Saint-Cirq Lapopie, and her fiancé, Richard Berberich accompanied her in the ambulance to the Toulouse hospital where she received treatment. But the young woman who opened her eyes 48 hours later, was not Marilyn Jensen. I was fascinated by her. She was suffering memory loss, but seemed to have adopted an entire personality, a persona in which she was comfortable. On a professional level, her case was intriguing. On a personal level, I sensed that I was entering very dangerous territory indeed.

|

Cliquez pour découvrir tous les titres de la collection