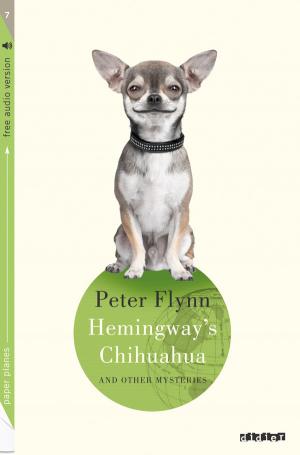

Ten extraordinary stories about extraordinary people. Some are true, some are completely fictional. But which? Did Einstein truly exchange places with his chauffeur at a physics conference? Does Queen Elizabeth play poker with her servants? And, of course, did Ernest Hemingway really have a killer chihuahua?

Ten extraordinary stories about extraordinary people. Some are true, some are completely fictional. But which? Did Einstein truly exchange places with his chauffeur at a physics conference? Does Queen Elizabeth play poker with her servants? And, of course, did Ernest Hemingway really have a killer chihuahua?

Amusing, beautiful, sensual, perturbing...TTen very different stories with one thing in common: each presents a fascinating mystery!

AUDIO VERSION

Einstein’s Chauffeur

The podium hides half my body but it can't conceal my trembling hands. I take a deep breath, place his glasses on my nose, and look down at his notes. They are in German. I can’t read German. Why? Because I’m from Pittsburg. I shouldn’t even be up here.

I look around the amphitheatre full of researchers: there are grey heads, white heads, bald heads and young heads with alert, enthusiastic expressions. A hall full of physicists who want to learn from me. I’m a chauffeur, and I’m here to teach Relativity.

I clear my throat and take a drink of water. At the back of the amphitheatre I see a familiar figure dressed in my dark chauffeur's uniform, sitting on a stool with my cap pulled down over his eyes. Even from here I can see his white hair. He sits up and I see the quick, childish smile come across his face. He sticks his tongue out at me.

Now the crowd is becoming agitated. There is a noise of chairs moving, and I'm thinking they can smell my fear, they’ve got to know what’s up. But now my boss is smiling and I can feel his warmth right from the back of the hall.

I can’t blame him. He didn’t force me to do this. I gave him the idea and he just…persuaded me. I’ve been driving him for a couple of months now, and one thing I can tell you for certain, it’s hard to say no to the professor. Just last week, as I was driving Professor Einstein back from a conference in Baltimore, I remember his calm Austrian accent coming from the back of the car.

“Harry, did you enjoy the speech I made this evening?”

“Oh, absolutely, sir.”

“Yes…I saw that you were enjoying it. I had a very good view.”

“Sir?”

“It appears to me that you were in a state of repose at the back of the auditorium. Is that correct?”

I slowed down a little, and glanced up at him in the mirror.

“Repose? What do you mean, sir?”

“You were asleep, yes. That is correct, is it not?”

I took a second to think about that. There wasn’t any anger in his voice, just curiosity. I guess you’d call it a desire for knowledge. His dark eyes were watching me in the mirror.

“Well, I wouldn’t say I was asleep—”

“Harry, we have, how do you put it…we have been on the road for some months now, yes? And although for many people across America my theory is new, you have heard me explain it at least twenty times, is that correct?”

“Twenty-three times, sir.”

He chuckled and slapped his knees. “Exactly. I can see it clearly. Now, you cannot read a book twenty-three times and expect to stay interested, can you?”

“No sir, I imagine that would be difficult.”

He sat back for a few minutes and I drove on through the rain. It was an easy drive back to the hotel, but I was going slowly as I thought he had something more to say.

“Harry,” he said at last. “Am I boring?”

“Oh no, sir.”

“But my speech is boring you, yes?”

“Oh no, Mr Einstein. I wouldn’t say that at all. I guess I’ve just heard the old Theory of Relativity so many times, I could give your speech myself.”

“Really?”

For a moment I thought I’d gone too far. He sounded angry.

“Please, prove it,” he said.

“Well, sir…” I began. And I gave him his introduction, word for word. He sat back in the seat, laughing softly.

“I don’t mean to be disrespectful, sir, it’s just that I have a good memory—”

“An excellent memory,” he said. “And what about the central theme, hmm?”

I gave him the rest of the speech, without having any idea what it all meant. I even did it with an Austrian accent, as I’d spent a long time sitting at the back of conference halls mouthing out the words as he said them.

“Fascinating,” he said when I’d finished. “I couldn’t have put it any better! I can’t blame you for falling asleep. I’ve often felt a little drowsy myself, saying the same thing each time.”

“But it’s important, Mr Einstein! I’m sure lots of people hang on to your every word!”

“Yes…”

“One day it could even make you famous.”

He sat back in the seat so I couldn’t see him, and we drove on for another few minutes. Then he bounced forward, wringing his hands in his lap, his eyes wide and childish.

“Stop the car.”

I pulled over to the side of the road, and we sat for a few minutes. I remember the sound of the rain on the roof, like a hundred ticking clocks, and the shape of the physicist in the back of the cab, thinking.

“I think we can have a little fun, yes? Some refreshment. We go to Dartmouth next week…no one there knows me, not yet…no one knows what I look like. So, why not you go and give the speech, and I take a little repose at the back, yes?” He pulled at his bow tie and smiled in the dark.

I should have said no. Straight away I should have slammed the door on the idea, but Professor Einstein is one of those people it’s very difficult to refuse. More than that, he's the kind of man who’ll make you believe you can do anything. Anything I found difficult he’d just laugh away.

Over the next three days Professor Einstein spent a great deal of time explaining Relativity to me in simple terms a child might understand. He drew me pictures of a lift in a skyscraper, then one of trains pulling away from another, and while I was no closer to understanding what the theory meant, his drive and his confidence were enough to make me agree to exchange clothes before we left the Dartmouth hotel, and he even persuaded me to let him drive us through the grounds of the university to the Physics Department.

So here I am at the front of this great hall, staring at the sheet of paper. I’m trying to remember what he told me in the hotel, but all I can see are trains and skyscrapers spinning away into a black hole. The other thing I can see is me getting discovered and handing my uniform to my boss for the last time. Einstein’s tweed jacket is tight around my shoulders, and only now am I aware of how much smaller he is than me.

The faces at the front are all enthusiastic and attentive; I see one young man, sharp-eyed like a fox, his pen poised over his paper. I take a final look at my chauffeur at the back of the hall. He’s already slumped in repose, his white hair frothing out from under his cap.

I begin.

I move through the speech, speaking slowly and carefully, not understanding a word I’m saying, but pretty soon I’m delivering the whole kaboodle word for word, just as we’d rehearsed it in the hotel. Just as the professor had told me, over and over again, “Don’t think, Harry, don’t think about it all. Just let the words come out in the right order.” At first I’m numb, beyond thinking, but pretty soon I’m forgetting myself and just giving a good performance. Before I know it I’m finishing and feeling very clever and flushed with success as I gather up Einstein’s notes.

Before anyone can stick up a hand to ask a question I’m rushing down off the stage, the professor’s papers clasped to my chest, the hall ringing with the sound of applause.

I could do this all week, I’m thinking. The hell with it. Let Einstein drive.

I see him stand up at the back, clapping delightedly, smiling like the proudest uncle in the world. As if in a dream I go towards him—

—and the fox-faced student steps in front of me, speaking breathlessly.

“Excuse me, Professor. I very much enjoyed your talk.”

“Why, thank you,” I murmur, trying to push past.

“Perhaps if you could just elucidate on one point…”

The clapping is dying down and soon the other professors and researchers can hear what’s being said. The Professor is now standing beside me but saying nothing. My knees are starting to tremble again, I feel the cold rise up in my guts once more.

“Elucidate,” I mumble. What does that mean?

I look over at Albert Einstein for help, but he just carries on looking proudly at me and not saying a word.

“Yes, sir,” the student goes on. “You see, you argued that the principle proposed by Newton…”

I lose him from there on in. I have no idea what to say, I can only let him finish and wait for him to find me out. I wish Professor Einstein would come out and rescue me, but he just takes out the car keys and says, in a terrible Pittsburg accent, “Shall I wait outside, sir?”

The student is waiting, his pencil is poised on his pad. I notice four other students waiting in the same way, their pens quivering like stings. Over their shoulders I see Einstein stick out his tongue again, and suddenly it feels like his voice is speaking through me, his words slow and patient and logical.

I look straight at the student and put on my best Austrian accent.

“The answer to that is very simple,” I say cheerfully. “Why, it’s so simple, I’m going to let my chauffeur answer it!”

The Mystery

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was born in the German Kingdom of Württemberg to a family of non-practising Jews. By the age of 10 he was reading Kant’s philosophical works as well as important mathematical texts. In 1921, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics.

It was Einstein who, during World War 2, convinced President Roosevelt that it was technically possible to build an atomic bomb and that the Germans might attempt to do so. As a result of his intervention, the Americans began the Manhattan Project, which culminated in the creation of the first atomic bomb and the destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Einstein, a pacifist and a particular lover of Japanese culture, was always troubled by his role in this.

During his career, Einstein travelled extensively around America and the rest of the world, lecturing on physics. He visited numerous American universities to talk about the theory of relativity but…

Did Albert Einstein really persuade his chauffeur to deliver a speech on Relativity?

Ask for another mystery!

|

Notes From The Maestro My only disappointment is that I never saw him until 1791. That was the year he died, and the year he saved me from starvation. I was forty-two and it had been many days since a warm meal had touched my lips. That February I drank the snow from the steps of the Vienna Opera House and dreamed of hot soup and meat. My only real nutrition came not from food or water, but music. Music! I used to sit on the golden steps of the opera house and wait for the great doors at the top to open, breathing in the beautiful sounds that came from within. Ah, the excitement of a clarinet concerto, released by a Philistine leaving the concert hall early, or the aroma of a cantata coming from a broken window— it was so hard to resist throwing a stone when there was so much happiness to be heard and tasted. It was all that was keeping me alive. Of course I knew I could never go in. Although I speak well, I have lived in this cape for fourteen years, my shoes are clinging to my feet and I smell of a decade of unwashed clothes. All I can do is sit on these steps and hope for charity from those lucky angels who can enter the hall, who can bathe in the serenades I can only taste, drop by drop, here in the heart of the Austrian winter. His music, of course, was sent to him by God. Since I first heard news of him as a boy, touring Europe with his father, angering the Vatican with his perfect recollection of their liturgies, I was interested in him. But only when I heard his early compositions, when I was a student myself in happier times, did I feel happy in a way I couldn’t explain. I could listen to his arrangements and endure all evil. As my position declined from a moderate family income to penury the composer grew more powerful, playing to emperors and audiences in Prague and England, and his name became famous everywhere. That didn’t mean anything to me until I sat outside on a night full of cold stars and sipped the notes I could hear coming from the broken window, or the rarely opened door. And even before that night in 1791 I was following his life through stories I heard in street markets; some too extraordinary to be true, such as his proposal of marriage to a young Marie Antoinette when he was a child. Or of the time he visited a farm when he was two years old, and when a pig squealed he cried “G-Sharp!” and the family ran to the nearest piano and found it to be true: a pig in G-Sharp. Like me, he has experienced prosperity, and I know he has tasted poverty, too. I know of that winter, not long ago, when his commissions stopped, denying him the luxurious life he had become accustomed to. I heard that on some freezing evenings he would dance a waltz with his wife, just to keep warm. That picture of him dancing with Constance came into my mind whenever I saw him hurrying to and from rehearsals at the Hall of Mirrors at Schloss Schönnbrunn. I was so sure it was him, a little man hunched up in thin clothes against the cold, but I never had the courage to act on my assumption, not until that night in February and I heard Die Zauberflote. I was enraptured, I was filled with the joy of his notes, and when the little figure came scurrying out of the great golden doors, I stepped in front of him. I was starving, you see. “Please, Herr Mozart,” I began, holding out a trembling hand. The woolen glove was frayed and wet from cupping snow to drink. The composer had looked flushed with success when he’d emerged, but now he seemed anxious. He wore a purple pelisse and a cocked hat laced with gold, but he seemed sick, haunted even. “What do you want?” His voice was soft, a tenor. “Just some money for some bread,” I said automatically, and felt humiliated by the words even as they came out. I bit my tongue. “I wish I had some money,” the composer said quietly. He kept his head lowered, a very thin, very pale man, with a puff of blonde hair and the vestiges of variola showing on his pitted face. “Please, I know you’ve been poor,” I said desperately. “I know you danced with Frau Constance just to keep her warm on penniless evenings, and your music has warmed me, it has warmed my very soul in the winter snow, Herr Mozart. I’ve danced with your music. It’s told me so much about grace and loveliness, I pray you might have just a penny for me.” At the mention of his wife Mozart looked up and his eyes were extraordinary. I’ve seen huskies in Vienna with eyes like blue fire, and Herr Mozart’s eyes were just such a colour. He looked straight through me; at the same time, his eyes were tinted with amusement, bright and alive. From a pouch he produced a sheet of paper, a tiny inkpot and a quill. Opening the inkpot, he pushed it into my hand, dipped the quill and began writing. There was something powerful and energetic about the way he wrote, something joyful and frenzied at the same time. Within minutes I saw a composition appear, black on yellow paper, like crows in a field of corn. When he’d finished he wrote a short letter, sealed it and gave me the sheet of music. “A minuet and a trio,” he said darkly. “Tomorrow morning you shall take it to the address on the envelope.” “But, I don’t know…how…” He gave a great childish smile at my confusion and walked off into the night. I stood for a few minutes, shivering under the stars, the precious paper hot in my hands. The notes were elegant and black, at once alien and imprints of the Divine. Notes from the master, I thought. Real music, original music, music composed for me! I held onto it all night. I slept with the composer’s ink still drying between my fingers, yet hunger drove me to the address of the publisher where, after much explanation, I exchanged Mozart’s composition for five guineas. That was the day that music brought me bread and meat and fine wine. I never saw Herr Mozart again, but now, whenever I hear one of his minuets, I remember his eyes the colour of fire, his ink on the golden page, his impulsive smile and the banquet he composed for me.

The Mystery

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) is among the most enduringly popular of all classical composers. A childhood prodigy, he began composing music at the age of five. The next years of his life were spent touring Europe with his father and sister, also musicians, performing for royalty wherever they went. As an adult, Mozart settled in Vienna, where his lifestyle was considerably more expensive than his income permitted. He was soon in deep financial trouble and this would remain a cause of constant anxiety, despite the success of operas such as The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni. In September of 1791, Mozart fell ill and died two months later. He was just 35 years old when he died, and in the course of his short life had composed over 600 works of music ranging from opera to symphonies and concertos, chamber, piano and choral music, but… Did Mozart ever write a short piece of music for a beggar?

|

Cliquez pour découvrir tous les titres de la collection