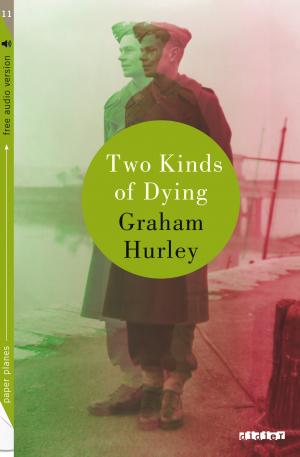

Normandy, 1940. Two young English soldiers find themselves plunged into war as France succumbs to the German army’s Blitzkrieg. Inexperienced and ill-equipped, they are soon taken prisoner. But this is just the start of their story as they are forced to march east across the country toward the prison camp that waits for them in Poland…

Normandy, 1940. Two young English soldiers find themselves plunged into war as France succumbs to the German army’s Blitzkrieg. Inexperienced and ill-equipped, they are soon taken prisoner. But this is just the start of their story as they are forced to march east across the country toward the prison camp that waits for them in Poland…

AUDIO VERSION

Introduction

This is an imagining. It was inspired by the events that surrounded my father’s death, and it’s based on months of reading, archival research, and face-to-face conversations. As Dad’s only daughter, for reasons that I still can’t explain to myself, it felt right for me to try and join the many pieces that comprise the strangeness of his life. The dates and the locations are real, as were the tides of history that swept him into captivity. The rest, I confess at once, is my version of what may have happened. The more I followed my father’s wartime journey, the better I felt I understood the man he became. That I may also have accidentally discovered a larger truth – that we are all the prisoners of our past – is for you to judge.

Chapter 1

Dad and Teazle

I first picture my father in the winter of 1939-40. I have a photograph, which helps enormously. He’s 19, skinny, on the short side, and absurdly handsome. The war is a couple of weeks old and he’s just answered the nation’s call to arms. The fact that he wears his beret at a defiantly jaunty angle, and that the top buttons of his khaki blouse are undone, suggests that he has yet to confront the darker realities of army life. In the background is the seafront at Clacton-on-Sea, which I remember from my own youth. My first real taste of fear was the afternoon Dad took me on the Big Wheel at the amusements. He loved fairgrounds and probably, at this point in his young life, regarded the war as one long free ride.

In the photo, Teazle stands beside him. He looks twice the size of Dad. Twenty mile route marches have yet to make any impact on his girth and he has the same blind faith that everything, the war included, will turn out just fine. One arm lies lightly across Dad’s slender shoulders. Like Dad, he’s playing up for the camera. These two men, in their sepia innocence, love each other.

The regimental depot for the 7th Royal Sussex Regiment is in Brighton, where both Dad and Teazle live. Neither of them have any money, an oversight that the war will do absolutely nothing to correct, but Dad has borrowed a handful of money from a mate, and he and Teazle have set out to drink it all. In later life, Dad loved a glass or two of beer, a habit that I like to think started early. It’s spring at last, after a savage winter. A strong rumour suggests the regiment are about to entrain for Southampton Docks, and thence to France. As it turns out, the rumour is true. This is the last time Dad will see the inside of an English pub for quite a while.

Dad adored pickled onions. He ate them all his life. There’s a big jar of them on the pub counter, and another one, full of pickled eggs, beside it. Teazle orders two of both.

“You’re crazy, you are. That cost a tanner,” Dad has a light voice, as you’d expect from someone with his physique.

“I’m starving, Joey. Here, I’ll get a couple for you.”

Dad says no. Why Teazle called him Joey remains – to this day – a mystery. “Teazle” is also a bit of a puzzle. His real name was John Parsons.

They share a corner table quite close to the door. Dad’s habit of always giving himself an escape route in life obviously started early. Pubs could be violent, especially with so many soldiers around, and Dad – despite the uniform and everything that went with it – never had much taste for violence.

“What d’you think then, Teaz? You think they’ll come? The Germans? Or have we called their bluff?”

Unlike most of the rest of the country, Teazle hasn’t given this proposition much thought. The army is three decent meals a day and the promise of foreign travel. He’s heard lots about France, chiefly to do with French women and French food. Both sound deeply promising, though he’s not sure about the garlic.

“Can’t wait,” he says. “You think we’ll strike lucky?”

Dad laughs. Only this morning he caught Teazle studying a school textbook that included basic French conversation. He’s memorised the French for “you’re so beautiful”, and “will you have a dance with me?”, and believes this happy combination will take him through to Paris. Dad, who was hopeless with languages, thinks Teazle’s accent is a joke.

“Worth a try though, eh Joey? A bloke in uniform? They won’t be able to resist me.”

He offers to let Dad come along the first time the regiment gets amongst French girls.

“You can hold my greatcoat, Joey. As long as you promise not to watch.”

“You’re joking, Teaz. You wouldn’t know where to start.”

“You don’t think so?”

“Never. Those Frenchie women will eat you for breakfast.”

The prospect of his two grand passions – food and sex – coming together on a wet night in Northern France does it for Teazle. He empties his glass, and orders another. He gets one for Dad but Dad’s had enough so Teazle ends up drinking for both of them. The pub is filling up by now and a bunch of soldiers in the corner have started to sing. Neither Teazle nor Dad know the words, which is just as well because Dad could never sing in tune.

Teazle drinks and drinks. By the end of the evening, in an alley round the corner from the pub, he’s being violently ill. Dad, who was always meticulous about detail, notes the curls of undigested onion and somehow gets him back to the regimental quarters where they’re all living. The duty sergeant puts Teazle on a charge – drunk and disorderly – and compliments Dad for holding his drink. Three days later, they’re all on a ferry heading south.

Ask for chapter 2!

|

Le Havre lies across the Channel from The regiment lands at Le Havre on April 21st, 1940. The men are trucked east, towards Picardy, and pitch camp in a village called Nontre. In a postcard to mum, which I managed to rescue before she started burning everything else, Dad writes about the pay and the weather. The blokes are getting 70 francs a week, which buys the odd jug of wine, and it’s been warm enough, he tells her, for everyone to be working with their shirts off. He’s digging lats and getting brown. Lats are latrines. Mum must have been thrilled. Today, Nontre is a dormitory for commuters working in nearby Rouen. Most of these people are far too young to have a clue about the last war but thanks to the local priest I managed to find an old man whose memory had survived the intervening years. Better still, the priest spoke decent English and offered to act as interpreter. The old man’s name was Pierre. He was a kid when Dad’s lot arrived and remembered coming home from school to find the area around the church covered with tents. “The soldiers were everywhere,” he told me. “This was the first time anyone really took the war seriously. Until then it had been a bit of a joke, une drôle de guerre. When the English came, my mother started getting really worried.” I was thinking about Dad and Teazle. Were there lots of young girls in the village? “Lots, yes. Most of the young men had gone to the army. That left the girls with nothing to do. “Were there dances?” “No.” “Did the girls go with the soldiers?” “Never.” “So what happened later? When the Germans arrived?” “That was different. They were here for years. Things happened. Things were bound to happen. The English? We woke up one morning and they’d all gone.” Disappointed, though a little wiser, Teazle and Dad are on the road again, smelling the dungy sweetness of rural France, wondering whether they’ll find richer pickings somewhere bigger. These apprentice soldiers – under-trained and under-armed – have been ordered to guard supply routes between the English Channel and British troops on the front line but the Germans are on the move now, bursting out of the hills and forests of the Ardennes and advancing at incredible speed towards the coast. The word on everyone’s lips is blitzkrieg. The drôle de guerre is well and truly over. Amiens lies directly in the path of the German The 18th May, 1940 is a Saturday. Dad and Teazle have swapped their truck for a cattle wagon, part of a long troop train. The train leaves a couple of hours after dawn and rolls slowly east towards Lens, up near the Belgian border. By mid-morning, there’s real warmth in the sun. The sliding door of the cattle wagon is open and some of the men sit on the edge, their legs hanging over the side. The rest doze inside. For the last eight days, since the German invasion of France and Belgium, training has been hard because shooting has started in earnest. Thousands of allied troops are already dead or taken prisoner and Teazle, in particular, has had to make room for something new in his young life. Fear. He and Dad, companionable as always, are sitting together. The cattle wagon is bumping and swaying on the single track and so far Teazle hasn’t touched his bully beef sandwiches. This tells Dad that something is seriously amiss. At first, Teazle denies it. He says he’s not hungry. He says he’s got a bug. But Dad has been watching him closely over the last couple of days and knows that his friend is lying. “What’s up, Teaz?” “Nothing.” “Tell me.” “Nothing to tell.” Dad is sucking a straw he’s found. He likes the taste. He gives Teazle a playful nudge in the ribs and tells him not to worry. Whatever happens, happens. There’s nothing either of them can do about it. Teazle lowers his voice. There’s a sergeant in the corner of the cattle wagon and it’s true what they say about NCOs1. They can smell a man who’s losing his taste for battle. “I was talking to a bloke in the armoury last night. You know how many bullets we’ve got? For each section?” “Haven’t a clue,” says Dad. “Four hundred.” Dad does the sums. Eight men per section. Fifty bullets each. “What about the rest of it? Grenades? Rockets? “You’re joking.” “Nothing?” “A few grenades. A couple of rockets. And lots of spades.” Dad gives him a look. He knows exactly what Teazle’s thinking. He’s imagining a bunch of “Too bad, Teaz,” Dad spits the straw out. “Like I say, whatever happens, happens.” |

Cliquez pour découvrir tous les titres de la collection